The Case of the Black Stone: A Scientifically Debunked Myth

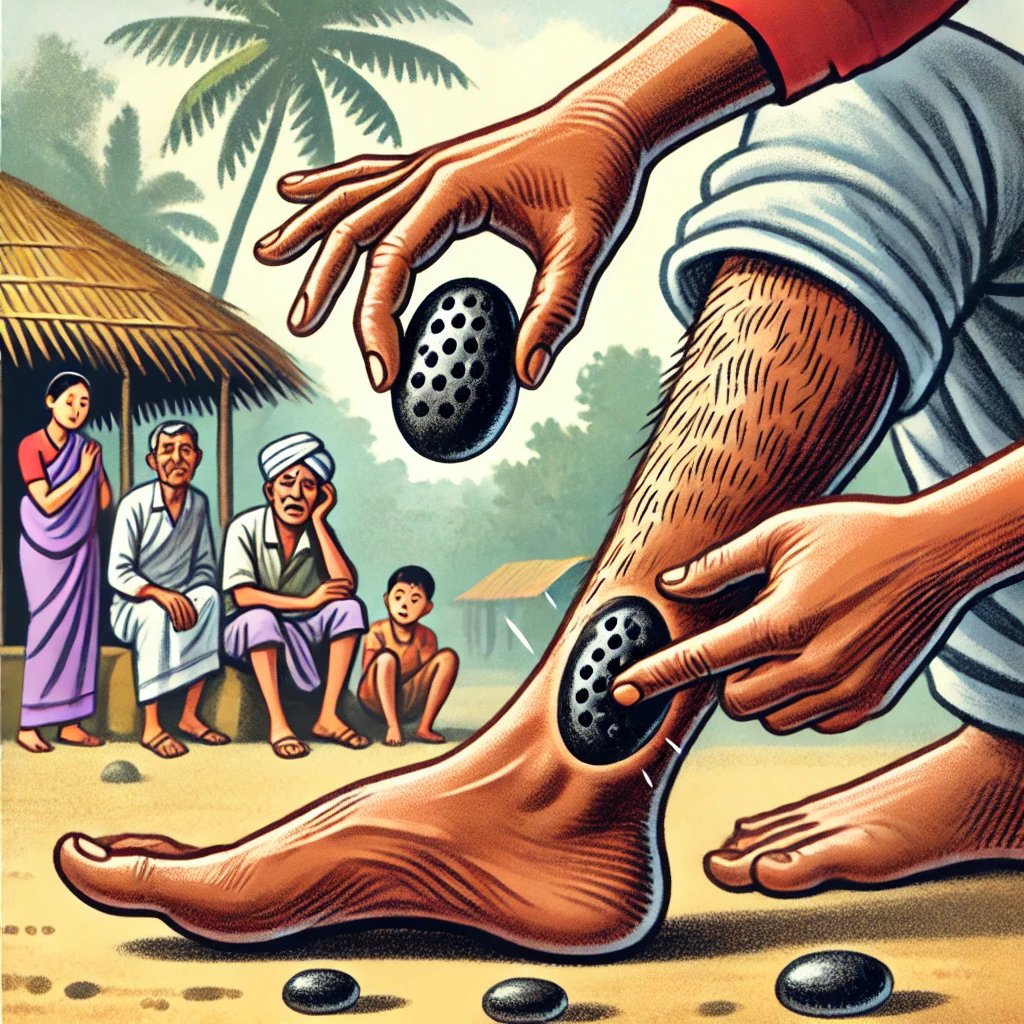

Snakebite envenoming is a significant medical emergency, particularly in rural areas of Africa and Asia where access to healthcare is limited. Traditional remedies, including the use of the "black stone," remain prevalent in many communities. The black stone, a porous piece of animal bone or plant-derived material, is believed to absorb venom when applied to a snakebite wound. Despite its widespread acceptance in traditional medicine, modern scientific studies have systematically debunked its effectiveness. This article explores the scientific evidence against the black stone, its risks, and the dangers associated with delaying proper medical treatment.

3/23/20253 min read

Lack of Venom Absorption

Proponents of the black stone claim that it has the ability to draw venom from a snakebite wound, thereby neutralizing its toxic effects. However, research has demonstrated that venom rapidly spreads into the bloodstream and lymphatic system upon envenomation, making local suction methods, including the black stone, ineffective (Williams et al., 2021). A study published in Toxicon found that venom injected into tissue diffuses within minutes, making it impossible for any external material to extract a significant amount once it has entered circulation (Williams et al., 2021). Furthermore, experimental trials using simulated venom applications on the black stone have shown no measurable absorption or venom neutralization.

Risk of Infection

One of the primary risks associated with the use of the black stone is infection. Since the stone is often applied directly to an open wound, it can introduce bacteria and contaminants that may lead to severe infections, including cellulitis, abscess formation, and sepsis (Habib et al., 2020). Many black stones are reused or stored in unhygienic conditions, further increasing the risk of bacterial colonization. In regions with limited access to antibiotics or sterile medical supplies, such infections can become life-threatening. Research in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases highlighted multiple cases where patients who used black stones subsequently developed secondary infections requiring intensive medical intervention (Habib et al., 2020).

False Confidence and Delayed Treatment

Perhaps the most significant danger posed by reliance on the black stone is the false confidence it provides to snakebite victims and their caregivers. Believing that the venom has been neutralized, many patients delay seeking proper medical care, which can lead to severe systemic envenoming, organ failure, and amputations (Gutiérrez et al., 2021). In many cases, venom-induced complications such as coagulopathy, paralysis, and tissue necrosis progress unchecked due to delayed antivenom administration. A review in The Lancet Global Health reported that patients who sought medical treatment within one hour of a snakebite had significantly better outcomes than those who relied on traditional methods before seeking help (Gutiérrez et al., 2021).

First-World Interventions: Suction Kits and Their Efficacy

Suction kits, commonly marketed in developed countries as emergency snakebite treatments, claim to remove venom from bite wounds if applied immediately. While these devices appear scientifically engineered, their effectiveness has been called into question by numerous studies.

Minimal Venom Removal

Scientific research indicates that suction kits remove only a negligible amount of venom, often less than 1% of the total injected dose (Bush et al., 2016). A controlled study published in Wilderness & Environmental Medicine demonstrated that even under optimal conditions, commercial suction kits extracted insufficient venom to make a meaningful impact on patient outcomes (Bush et al., 2016). Since venom diffuses into surrounding tissues rapidly, attempting to remove it mechanically is largely ineffective.

Potential Tissue Damage

Beyond their inefficacy, suction kits can exacerbate tissue damage. The force exerted by these devices may increase localized bleeding and tissue necrosis, worsening the injury rather than improving it. Studies have reported cases where improper use of suction kits resulted in secondary infections and aggravated wound severity (Bush et al., 2016). This risk is particularly concerning in environments where medical attention may be delayed due to reliance on ineffective first aid measures.

False Sense of Security

Much like the black stone, suction kits provide a dangerous false sense of security, potentially discouraging victims from seeking appropriate medical intervention. Many users believe that venom extraction via suction mitigates envenomation effects, delaying essential treatments such as antivenom therapy and supportive care. Public health initiatives have recommended against the use of suction kits, advising instead for proper wound immobilization and rapid transportation to a medical facility (WHO, 2023).

Conclusion

Despite its cultural significance, the black stone has no scientific validity in treating snakebite envenoming. The belief that it can absorb venom is unfounded, and its use can lead to serious complications, including infection and delayed medical treatment. Similarly, first-world interventions like suction kits have been proven ineffective and potentially harmful. The most effective strategy remains immediate immobilization of the affected limb and rapid transportation to a healthcare facility where appropriate antivenom can be administered. Efforts should focus on community education to dispel myths surrounding ineffective treatments and promote evidence-based medical interventions.

References:

Bush, S. P., et al. (2016). "Snakebite suction devices: A review of efficacy and risks." Wilderness & Environmental Medicine.

Gutiérrez, J. M., et al. (2021). "Snakebite envenoming: A global public health challenge." The Lancet Global Health.

Habib, A. G., et al. (2020). "Challenges of snakebite management in Africa: Need for an integrated approach." PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.

Williams, D. J., et al. (2021). "Debunking the black stone myth: Scientific evidence against its use in snakebite management." Toxicon.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2023). "Snakebite envenoming: Key facts and global response." WHO Report.